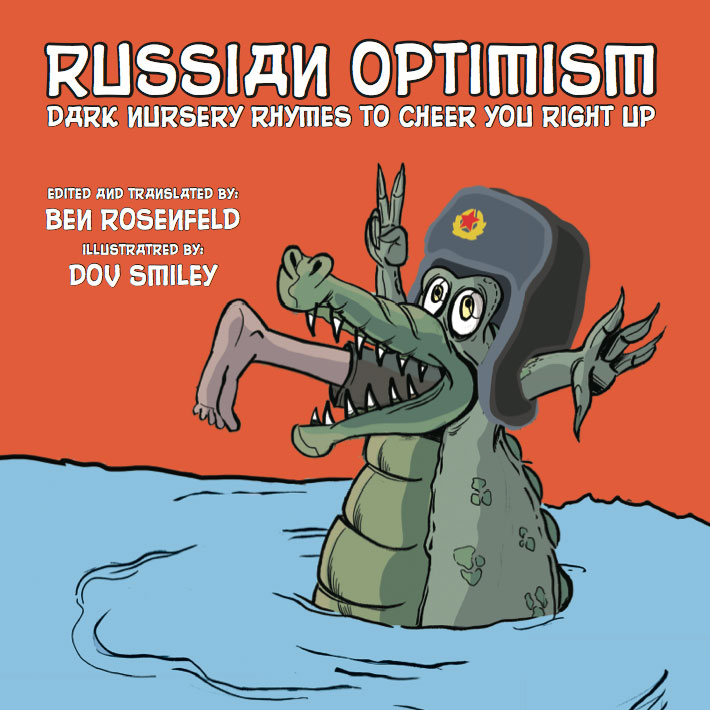

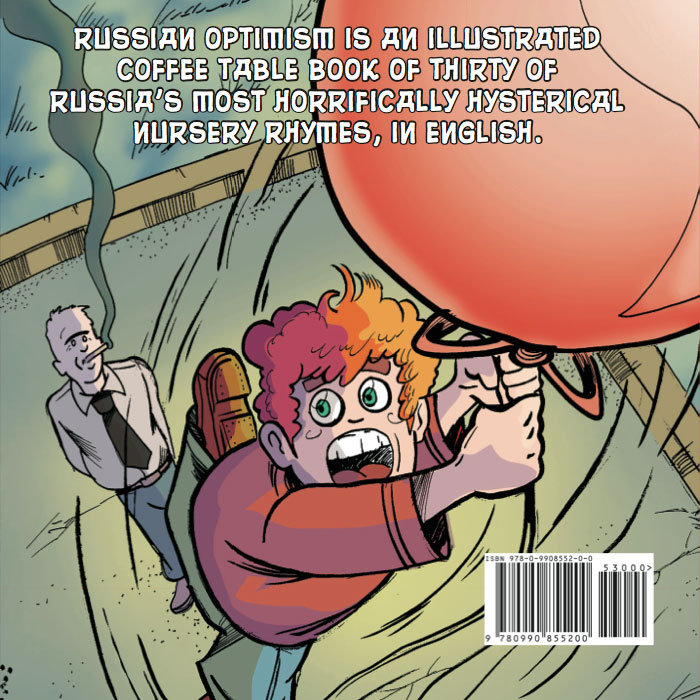

In 2014 I did a Kickstarter campaign to create the illustrated coffee table book, “Russian Optimism: Dark Nursery Rhymes To Cheer You Right Up.” I wound up surpassing the fundraising goal and within five months the book was published. I would like to share my lessons learned and offer advice for those who are interested in self-publishing a book.

In 2014 I did a Kickstarter campaign to create the illustrated coffee table book, “Russian Optimism: Dark Nursery Rhymes To Cheer You Right Up.” I wound up surpassing the fundraising goal and within five months the book was published. I would like to share my lessons learned and offer advice for those who are interested in self-publishing a book.

PREPARATION PHASE

- Create A Pitch for Literary Agents

After speaking with a friend who works in publishing, I spent time putting together an agent query letter, a ten page book proposal and a spreadsheet of agents to pitch. Why am I suggesting this when I wound up self publishing? Because:- 1) This forced me to write a clear, concise, one page and ten page document summarizing my book, my target audiences and my marketing ideas. Later on when I created the Kickstarter page, I was able to copy and paste from the book proposal document instead of starting everything from scratch.

- 2) Unlike many people in film and TV, most literary agents get back to you fairly quickly with a decision on whether or not they want to see more of your book. If an agent likes your book and can get you an advance, it might still be worth going the publishing house route. (While perhaps still combining it with a Kickstarter to build a fan base before the book is released.)

- Create a Video

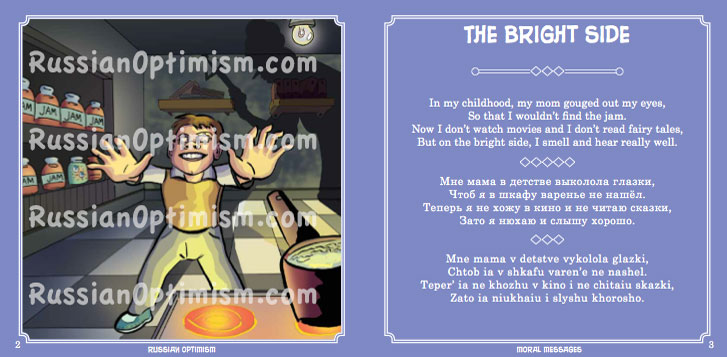

I put together a three and a half minute video explaining the project, giving examples of the content and talking a little about myself. The video shows potential donors that you’re passionate and committed to putting something together that looks professional (make sure to post a high quality video!). This helps convince potential donors to entrust you with their money. - Create as Many Mock-ups As Possible

Before seeking potential donors, I spent my own money to create sample illustrations. If you don’t believe enough in your project to invest seed money, why should anyone else? I put the sample illustrations into a mock-up spread with text, so people would get a feel for how the completed book would look. (The final book came out much better than the mock-ups, keep reading to see why.) You should definitely create as much of the look and feel of your book as possible for the Kickstarter page. This is particularly recommended for illustrated or photo-based books, but use your own judgment for your book. - Shorten and Re-Edit Everything, Including Reward Levels

My first draft of the Kickstarter page had way too many reward levels. The description of the project was too long. I listed too many “potential problems.” Go through your entire Kickstarter page and get rid of every word that’s unnecessary. Then do it again. Then again. Then do the most important thing you can do– - Get Feedback From Smart & Trusted Friends Before Launching

I sent the Kickstarter page to eighteen friends whose opinions I trust, asking them to look over my page for general comments and to answer two specific questions:- 1) What do you think of the rewards? Is any reward unclear?

- 2) What do you think of the project description? Is anything unclear? Unnecessary?

- Nine friends responded with varying levels of detailed notes, which all helped make the project as clear as possible. A side benefit was two of those nine friends contributed money to the actual campaign, including one for a really high reward level. When you ask people for help, they become invested in your project.

- Send the page to people you trust for notes, but avoid people who are overly negative or overly positive, you need specific notes, not just “this is great” or “what are you doing with your life?”

- Figure Out Your Funding Goal By Pricing Out The Costs

There’s going to be one-time fixed costs (an illustrator, a book designer, ISBN registration, publishing upload fees) and variable costs (how many books you print and the mailing cost per book). Once you’ve researched your fixed costs, figure out how much you’d need to charge per book and how many books you’d need to sell to cover those costs. That’s a rough estimate for how much your campaign needs. (I approached this project with the goal of breaking even from Kickstarter and hopefully making money later on from additional sales.) Then remember Kickstarter’s and Amazon’s fees will eat into the money you raised. For example, I raised $3,800 but after fees I only received $3,300. So add 20% to your previous number for the goal. Also, have an amount of money you’d be willing to lose to make your project happen. And charge a lot for international shipping (see towards the ends of this post for the full explanation).

DURING THE KICKSTARTER CAMPAIGN

- Have a Daily Promotional Plan for All 30 Days

Before launch, I identified potential audiences that might like this book: Russian speakers, illustration fans, people with a dark sense of humor. Then I wrote down a daily action plan to raise awareness for my Kickstarter campaign and divvied that up into thirty, more manageable, daily tasks. I devoted 30-60 minutes per day for this campaign. Some days I would post it on specific Facebook groups, other days it was on reddit, I also included in my monthly mailchimp newsletter. The point is, do something every day. - Don’t Rely On Only Your Friends for Funding / Expand Your Fundraising cirle

Your friends will (hopefully) help you, but you can’t rely on only them. The first financial contributions were made by friends. Their donations gave legitimacy to the project and then strangers started to contribute. By the end of the campaign, only 30% of the donors were people I knew. - Getting Your Kickstarter Project On The Right Blog(s) Makes A Huge Difference

An early contributor of mine submitted my project link to BoingBoing.net and next thing I knew, lots of strangers were contributing to my project. Figure out who your target demographic is, what sites they frequent, and post on those sites. - Mention Your Project In Most Conversations (Without Being Annoying)

You never know who might be interested in the subject matter of your project. So when you’re going about your normal life and people say “hey, what’s up?” Instead of saying nothing, mention you’re working on a Kickstarter project. If they don’t ask more about it, let it go. But if they ask, this is a great time to spread awareness about the book and its campaign.

CREATING THE ACTUAL BOOK

- Pay For a Book Designer

Seriously, this is the best money you’ll spend. I was on the fence but decided to spend the extra money. Once I started working with the designer, I realized how much time I had saved myself by not trying to do it on my own. A good designer is worth his price a hundred times over. Your book ends up looking better because a book designer will think of little things you would have never thought of: different text separator designs, formatting decisions, etc. This will make your original funders happier and more likely to tell people. And the book becomes easier to sell to new customers. - Buy The ISBNs

If you want to be listed on Amazon, Barnes and Noble and every other online (and potentially retail) store, you must spend the extra $250 and get the ISBN. This also makes your book look much more professional. With an ISBN there’s at least a chance that brick and mortar bookstores will stock it too. - Build In Lots of “Oops Time”

I was funded by the end of June. My illustrator said it’d take him six weeks to do the remaining drawings. My book designer said he’d need a month. My printing company said they’d need three weeks. If I had taken everyone at face value, I would’ve promised this book to people by October. But I knew better, and built in two extra months for when things will inevitably get delayed. You’re always better off leaving extra time and pleasantly surprising people than cutting it close, being late and making people angry. Plus the extra time allowed me to order one test copy of the book, where I found lots of little typos. Oh and if your Kickstarter succeeds and you have to ship hundreds of books, guess what, that’s a huge time suck! So leave time for that too. - Quadruple Check For Typos

My only real complaint with self publishing is that the print-on-demand companies gouge you with fees if you have to re-upload any corrections. IngramSpark charges $25 per re-upload, and the cover file is a separate fee than the interior files. That’s $50 every time you catch a mistake late in the process. (And you will almost always catch some last minute mistakes.)After everything seemed fine and I’d placed an order for 150 copies, a friend of mine was looking over the book and found 7 more typos. 7! Including 2 on the cover! Luckily, I called customer support and they were still able to make the changes before printing, but I almost had heart attack. And it cost me an extra $50. Ask everyone you know who is willing to spell check and grammar check your book before you send it to print. If you’re doing something that’s more text heavy, pay for a professional editor. Also, you save $25 if your ebook version is ready at the same time as you upload your print version.

GETTING THE FINISHED PRODUCT TO KICKSTARTER CUSTOMERS

- International Shipping Blows

Financially this has been my biggest miscalculation to date. I had no idea how much international shipping (from the US) costs. I knew it might be a little more, so I had international funders add another $5 for shipping. (My basic book price of $25 included shipping to America, which I had properly estimated at $5.) Turns out sending a book overseas (not counting Canada) is $18.65. I lost 8 dollars per book I sent out. So if you listen to nothing else I’ve said, listen to this: Charge an extra $20 for international shipping. - “Wow!” Your Kickstarter Customers

Give more than what you promised, even if you lose a little money. These are the people who believed in you most, reward their loyalty. I included a free copy of my comedy DVD with each book, as well as a Russian Optimism bookmark and a hand signed thank you letter. I want my first 106 customers to be really, really happy and to show and tell all of their friends. You should want that too.

AFTER CROWD FUNDING

- Be Ready To Sell More

While it may feel like the end, if you care about your book (and your bottom line) you will realize this is only the beginning. You need to figure out how to get people to talk about your book and (more importantly) to buy your book. - Have Your Marketing Plan Ready Before Sending The Book To The Printer

This is the biggest mistake I’ve made so far. I didn’t fully formulate my post-Kickstarter marketing plan until after the book was already available on Amazon. (My printer told me it usually takes Amazon six to eight weeks to list the book, it took two.) The day after I saw the book for sale on Amazon, my physical books arrived that I had to send out to my Kickstarter funders. I am now behind on generating new sales as it took me four days to ship out all the existing orders. I also lost money by printing my bonus bookmarks locally to save time rather than ordering online.

Hopefully you found this helpful. If you have any other questions, feel free to contact me – I can do a private consulting session on your book project.

Thank you to Charlie Hoehn, Ryan Holiday and Tim Ferriss for inspiring me to share my lessons publicly.